The following is an approximate transcript of the Dharma Talk that I offered at part of O-An Zendo’s Sunday Program on July 7th, 2024. You can also listen to a live recording of the talk.

Enjoy.

Whether you have been around for a long while or a little while, you have likely heard the following chant:

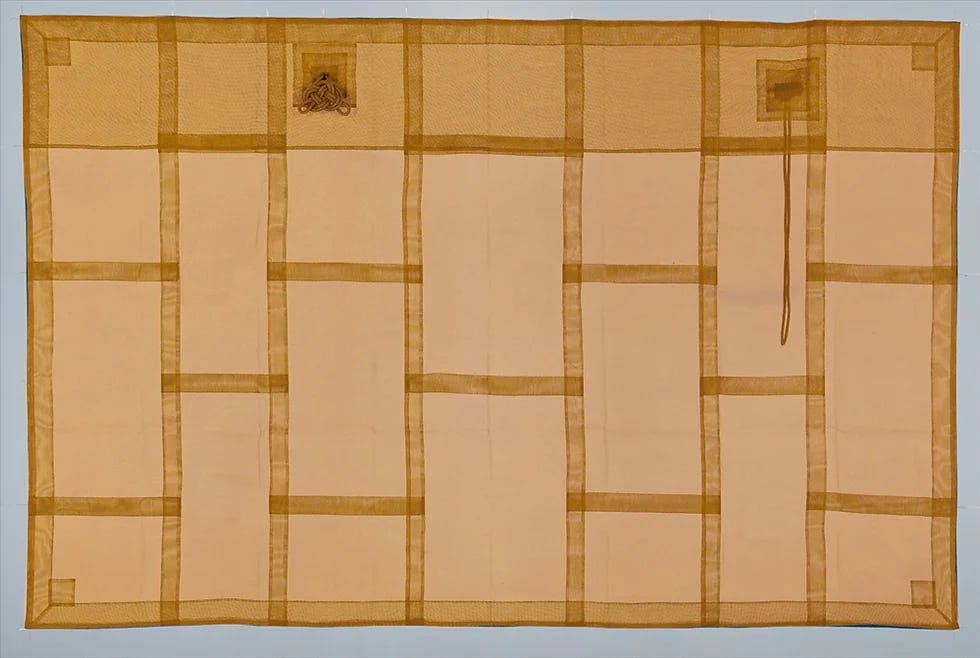

Dai sai ge da pu ku mu so fuku den-e hi bu nyo rai kyo ko do sho shu jo. Great robe of liberation field far beyond form and emptiness wearing the Tathagata’s teaching freeing all beings. Dai sai ge da pu ku mu so fuku den-e hi bu nyo rai kyo ko do sho shu jo.

Sometimes, we call this “The Robe Chant.” Other times, we call it “The Verse Of The Kesa”; kesa is the formal term for an ordained person’s robe.

The verse is recited during ordination ceremonies before the ordainee puts on the robe, whether a rakusu or an okesa. Some of you witnessed Ronin, Daigen, and Myoshin chant these lines during their Jukai ceremonies, after which Roshi removed a rakusu from the top of their head and placed that rakusu around their neck.

Some of you heard An Gyo and I chant the verse during our Shukke Tokudo ceremonies and then saw me, in the case of An Gyo’s priest ordination, wrap, tie, and tuck the okesa around him. During my priest ordination, you saw my now-former sponsor Jim and Dharma sister Nenzen Pamela Brown, Sensei, do the same for me.

Recently, we heard Jiko, Meiju, and Senshu chant together The Verse Of The Kesa during their Jukai ceremony. In the near future, you can hear Daigen recite it during his Shukke Tokudo and Andrea during her Jukai. And I hear that another four to six sangha members are interested in receiving precepts. There seem to be many opportunities to hear The Robe Chant on the horizon. We may begin chanting it during early zazen on Sundays, too.

For those of us who have been ordained and have robes, we also chant The Verse Of The Kesa each day before we put on our rakusu or okesa, and we do this whether we are here at O-An Zendo or in our home and always before we sit zazen. Always.

Sometimes, we hear the instruction, “Sit zazen and think not-thinking. How? By not thinking.” Other times, we hear, “Sit zazen and drop off body and mind.” When we hear these instructions, it is understandable if our heads tilt to one side, expressing puzzlement. What do you mean by “think not-thinking”? What do you mean by “drop off body and mind”? How do I do either of those things?

Kodo Sawaki, Roshi—who, by the way, was the zazen teacher of our lineage holder, Kobun Chino, Roshi—offered something different to his students, saying, “Wear the kesa and sit zazen: that is all.” There is nothing else to do but wear the kesa and sit zazen.

If nothing else, Sawaki Roshi’s instruction appears straightforward. Yet, for me, it raises a question that The Robe Chant itself also raises. What does it mean to “wear the kesa”? What am I committing to when I recite The Verse Of The Kesa and say, “wearing the Tathagata’s teaching”? These are the questions I want to ask this morning:

What does it mean to wear the kesa?

What am I committing to when I say “wearing the Tathagata’s teaching”?

From one point of view, there is a response as straightforward as Sawaki Roshi’s instruction. The final line of The Robe Chant is “Freeing all beings.” That is what it means to wear the kesa, to be part of a collective effort to free all beings from suffering. That is what we commit to when we say “wearing the Tathagata’s teaching”: to participate in the great effort of freeing all beings from suffering.

Here, the commitment expressed in The Verse Of The Kesa is not limited to those with physical robes or who have participated in special ceremonies. It is open to all of us, and arguably, all of us commit to it when we recite the Incense Offering at the beginning of service.

In gratitude, we offer this incense. May all beings with whom we are inseparably connected be liberated, awakened, healed, fulfilled, and free. May there be peace in this world, and an end to war, violence, poverty, injustice and oppression. And may we, together with all beings, complete our spiritual journeys.

May all beings be liberated, awakened, healed, fulfilled, and free. May there be peace and an end to war, violence, poverty, injustice, and oppression. May we and all beings complete our spiritual journeys.

The above are only different ways of saying that we commit to participating in the great effort to free all beings from suffering. And I felt it imperative to draw your attention to this because, although I am focusing on The Robe Chant this morning, I am talking to everyone here.

I wonder if when you recite The Verse Of The Kesa or hear it, or when you chant or hear the Incense Offering, the word “all” stands out to you. I wonder if you feel the heaviness the word can bring and how weighty the commitment to participating in the great effort to free all beings from suffering sometimes is.

I do—I can assure you of that. Sometimes, including this past week while preparing this talk and the last couple of weeks, during which I have been practicing with strong emotions, I have felt that I do not want to free all beings from suffering. At least, I do not want to free all beings yet.

Who, specifically, do I not yet want to be free from suffering? Some have bullied me and continue to do so from time to time. When we hear of someone “being a bully,” we imagine the school playground. As all of us are aware, though, bullying continues well beyond our childhood years and into adulthood. Its form changes, the particular ways it appears in relationships, but its spirit is the same whether it takes place behind the jungle gym or in an office building. The same goes for those whose behavior I would not describe as “bullying” but as “harassment.”

Then, there are the people who have abused me, including two previous romantic partners. In neither case was the abuse physical; in both cases, the abuse was emotional and verbal. Do I need to help free from suffering the person who used me as a (verbal) punching bag? Who screamed with rage at me, and for or about things that I was not involved with, when I was not even in the same state? What about the person who made me feel like I was “walking on eggshells”? No matter what I said, it was the “wrong thing,” and the tirade would begin. Being silent did not help, either. Being silent instead of speaking was also the “wrong thing,” and in just the same way, the assault would get underway. Who succeeded in manipulating me, gaslighting me—do I need to commit to freeing them, too?

And what about those who have sexually harassed me? Those who wanted something more than my bare attention or to use me as an outlet for their frustrations? Who pursued me to get what they wanted and, in some cases, cornered me and took it? In these cases, it is not so much not honoring the gift not yet given but taking that which was not even willing to be given in the first place. Do I also need to help free them from suffering?

It is difficult for me to practice with the people that fall into these categories. There is too much energy; my emotions are challenging to handle at best and downright unwieldy at worst. Sometimes, I feel that I am a loose canon, liable to fire without hesitation in any direction.

And yet, these people, who have bullied and harassed me, who have abused me, and worse, even them, when I recite The Verse Of The Kesa and put on the Okesa, I commit to freeing from suffering.

Wearing the Tathagata’s teaching

Freeing all beings

Most of the time, I carry out this effort “indirectly.” I want to say a bit about how I do that now.

When I can sit with what arises in connection with very challenging people in my life, I see that resistance to being of service to them springs in part from what I will call a “strong sense of fairness.” It has an “eye for an eye” quality to it. Why should I help you, given how you have treated me? I will help free you from suffering, but not yet.

This “strong sense of fairness” appears in other areas of my life. For example, I am the oldest of four children. There are some things that people say are typical of the oldest child, and some of those things are likely true of me.

One of them is that the rules applied to me when I was growing up in a way that seemed not to apply to my younger brother and two younger sisters. Never or rarely would I “get away with” what they did; punishment was sure and swift whenever I talked back or otherwise misbehaved. At times, I would wonder, “Why was I subjected to various forms of physical punishment while they were largely or wholly exempt? Why could I not be spared my father’s large hand or my mother’s wielding of the wooden spoon?” Seeing that different standards applied to my siblings, and for reasons I could not discern, was upsetting. I am confident that I thought or said more than once, “It is just not fair!”

During my years as a graduate student, I resented many comrades who asked for extensions for their term papers or incompletes for a course. It was my understanding that the deadline for submitting a term paper was such-and-such a date, and that was the deadline unless there was an outstanding circumstance. Routinely, however, others would ask for another week or to submit sometime next term because they wanted to go camping, the waves off a nearby beach had been too good to miss, a show was happening in Los Angeles or San Francisco, or whatever. The point is that I judged these not appropriate outstanding circumstances. I would have liked to do these things, too, but there was a policy, and I thought we had all agreed to it.

Here, too, I found the different standards upsetting, and often, I would wonder, “Why does it seem as though the deadline applies only to me? This is unfair!”

It goes in the other direction, too, by the way. I will spend a week at Ancestral Heart Zen Temple in Millerton, New York, in August. The residential training temple is part of the Brooklyn Zen Center’s network, and a new friend serves as its Director.

I reviewed the Shingi (Temple Regulations) for Ancestral Heart. Much of the document is standard: dress in these ways at these times, observe silence between these hours, refrain from these sorts of activities or behaviors, and so on. There was one section that caught my eye, however; currently, I have nine facial piercings.

Please keep hair off your neck and refrain from wearing scented lotions, perfume, nail polish, makeup, jewelry, watches, or mala beads in the zendo. While watches and lotions may be required at times, it is requested these same guidelines be followed at all other times while living in residence. Jewelry associated with former vow-taking ceremonies, e.g. wedding rings, can be worn at all times.

I wrote to the Director to confirm that I understood the Shingi correctly. I said that I would need to withdraw my application for short-term residency because I want to respect and uphold the policies that support practice at Ancestral Heart. I do not need or want to be an exception; I do not need or want special accommodations. If this is the policy, I cannot agree to it, and I will quietly find elsewhere to visit and practice. “That is what is fair. That is what is appropriate,” I thought.

And I share all of this because it is much easier for me to get close to the “strong sense of fairness” in these cases. Some of them were without a significant emotional charge from the beginning; for others, the emotional charge has diminished with, though not because of, time. As a result, I can sit with what happened without great difficulty—the sort of difficulty that obstructs insight. What is behind this fixation with fairness can begin to show itself. Then, I can start practicing with it.

Shunryu Suzuki, Roshi, opened a Dharma Talk with the following:

In our service after reciting a sutra, we offer a prayer to dedicate the merit. According to Dogen Zenji we are not seeking for help from outside because we are firmly protected from inside. That is our spirit. We are protected from inside, always, incessantly, so we do not expect any help from outside. Actually, it is so, but when we recite the sutra, we say a prayer in the usual way. […] We do not observe our way, or recite our sutra to ask for help. That is not our spirit. When we recite the sutra, we create the feeling of non-duality, perfect calmness, and strong conviction in our practice.

If that kind of feeling is always with us, we will be supported.

I want to offer two examples if it is all right with you.

There is a chant that means a lot to me: Eihei Koso Hotsuganmon (Dogen’s Vow). In the middle of the chant, it reads:

Although our past evil karma has greatly accumulated, indeed being the cause and condition of obstacles and practicing the way, may all buddhas and ancestors who have attained the Buddha Way be compassionate to us and free us from karmic effects, allowing us to practice the way without hindrance. May they share with us their compassion, which fills the boundless universe with the virtue of their enlightenment and teachings.

Here, with recognition of the obstacles we meet in practice, we ask for help from all buddhas and ancestors. “Share with us your compassion; enable us to practice without hindrance,” we say. Yet, even though we say this

We do not observe our way, or recite our sutra to ask for help. That is not our spirit. When we recite the sutra, we create the feeling of non-duality, perfect calmness, and strong conviction in our practice.

As part of our Sunday service, the Dōan chants, following the invocation of Shakyamuni Buddha, Mahapajapati, Bodhidharma, Eihei Dogen, ancestors in the Phoenix Cloud lineage, and several Bodhisattvas:

We vow to return their compassion and carry it to the future. May the merit be directed towards: Lasting peace in the sangha Tranquility of daily practice Dissolution of all misfortune Fulfillment of all relations

Again, it appears that we are asking for the merit of our practice here today to help bring lasting peace and tranquility, dissolve misfortune, and bring fulfillment.

Although we say this prayer

According to Dogen Zenji we are not seeking for help from outside because we are firmly protected from inside. That is our spirit. We are protected from inside, always, incessantly, so we do not expect any help from outside. Actually, it is so, but when we recite the sutra, we say a prayer in the usual way.

It seems to me that Suzuki Roshi’s teaching applies not just to reciting sutras and prayers. It also applies to “strong senses of fairness”—or your particular hangup, whatever that might be.

Behind this sometimes obsession with fairness is fear, in my case. I suspect that it is fear for you, too, and that is why you need to be in control, seen as wise, special, or strong, why you refuse to take anything seriously or, once more, whatever your particular hangup is. Fear that, if things are not fair and people do not abide by various policies and rules, then I will, as Koan Gary Janka, Sensei, would put it, “end up alone, cold and shivering, underneath a bridge, in the rain and the dark, with my cat, dead, in a shoe box.” “It always terminates there,” he would often tell me.

And just as it is not part of our spirit to expect help when we recite sutras or dedicate the merit, it is not part of our spirit to expect help by enforcing fairness, trying to hold onto control and remain in power, acting in ways that encourage people to see us as wise, special, or strong, or turning everything into something light and joke-worthy. We do all of these things, however, instead of creating a strong conviction in our practice.

If that kind of feeling is always with us, we will be supported.

Then, there is nothing to fear. When there is nothing to fear, we can wear the kesa and carry out that commitment at the heart of The Verse Of The Kesa:

Great robe of liberation field far beyond form and emptiness wearing the Tathagata’s teaching freeing all beings.

Freeing all beings. To wear the kesa is not to step up but to step down—to step down into service to others. To wear the Tathagata’s teaching is to set aside personal preferences and expectations; it is to understand that, in wearing the robe, it is not about you. And it takes great courage, fearlessness, and deep understanding that we are supported from within to do this.

It is about all beings. Freeing all beings. That is our commitment. That is our vow.

If you benefitted from this offering, you may enjoy reading:

"According to Dogen Zenji we are not seeking for help from outside because we are firmly protected from inside. That is our spirit. We are protected from inside, always, incessantly, so we do not expect any help from outside."

What does this mean? Never heard it said this way. What (allegedly) protects us? Or is it something that enables us to protect ourselves? Not a person of faith myself, and all those religious promises of "protection" and "comfort" rang hollow to me. Buddhism has been unlike any other religion in that it didn't blow smoke up my ass, or fabricate castles in the air, but I'm trying to find...refuge, I guess. I can say "I take refuge," but it means nothing to me. How do I build a foundation of security and right thought when my soul is nothing but sand?