The following is an approximate transcript of a Dharma talk that I offered on Saturday, July 27th, during O-An Zendo’s Udumbara Sesshin. You can also listen to a live recording.

Enjoy.

Almost one year ago, I sat in this seat and offered a Dharma talk on the topic of the transmission of the teachings. Specifically, I spoke about the first transmission of the Dharma from Shakyamuni Buddha to Mahakasyapa and began with an excerpt from Dogen’s Shobogenzo Menju (Face-To-Face Transmission). Since that talk went well, I will begin this talk in the same way.

Dogen writes:

Shakyamuni Buddha graciously entrusted and transmitted the Dharma face to face to Mahakashyapa, saying, “I have the treasury of the true dharma eye. I entrust it to Mahakashyapa.”

At the assembly of Mount Song, Bodhidharma said to Huike, who would later become the Second Ancestor, “You have attained my marrow.”

From this we know that entrusting the treasury of the true dharma eye and saying, “You have attained my marrow” is this very face-to-face transmission. At the exact moment of jumping beyond your ordinary bones and marrow, there is the buddha ancestor’s transmission face to face. The face-to-face transmission of great enlightenment, the face-to-face transmission of the mind seal, is extraordinary. Transmission is never exhausted; there is never a lack of enlightenment.

Now, the great way of buddha ancestors is only giving and receiving face to face, receiving and giving face to face; there is nothing excessive and there is nothing lacking. Faithfully and joyously realize when your own face meets someone who has received this transmission face to face.

Whether you are hearing this excerpt for the first time, the second time, or the some-number-greater-than-two time, you might have the impression that transmission of the Dharma happens when someone in possession of the Dharma gives the Dharma to someone who is not in possession of the Dharma. You might understand the transmission of the Dharma in the same way you understand someone entrusting a family heirloom to another member of the family, the way a grandmother might entrust a gold locket to her granddaughter, for instance. The grandmother is in possession of the gold locket, and her granddaughter comes into possession of the gold locket when the grandmother transmits it from her hands to her granddaughter’s hands, perhaps accompanied by some words chosen for the occasion.

I have the treasury of the true golden locket of the Jones family, and I entrust it to Betsy! I wager that no grandmother has ever said this, probably.

This is one way of understanding what happened when Shakyamuni Buddha held up a flower, Mahakasyapa smiled, and then the Buddha said, “I have the treasury of the true dharma eye. I entrust it to Mahakashyapa.”

This impression is reinforced by the way our excerpt closes. Dogen writes that this great way of buddha ancestors is nothing other than giving and receiving face to face, receiving and giving face to face. One has, the other does not; one gives, the other receives. Furthermore, sometimes we describe this giving and receiving as happening mind to mind, heart to heart, and warm hand to warm hand—again, not much different from the way a grandmother might entrust a family heirloom to her granddaughter.

Yet, this is not the only way to understand the first transmission or transmission of the teachings generally. Bodhidharma’s expression “You have attained my marrow” suggests less giving and receiving from a “has” to a “has not” and more an acknowledgment of a shift or transformation brought about by Huike’s great effort and sincere practice.

There is also the expression “jumping beyond your ordinary bones and marrow,” which happens at the exact moment in which the Dharma is transmitted. Who can jump beyond your ordinary bones and marrow but you? Where can this leap occur but wherever you are when it happens? You may not feel yourself jump or leap, though you do not need to. Your teacher will recognize it in the same way that Bodhidharma did for Huike: “You have attained my marrow.”

From this point of view, transmission is not exclusively something that happens from without. Instead, transmission also includes that which arises from within.

Some weeks ago, I offered a Dharma talk on Dogen’s Shoaku Makusa (Refraining From Evil), which opens with the following gatha:

Refraining from committing various evils Carrying out all sorts of good actions Personally clarifying this mind This is the essential teaching of all the buddhas.

Then, several lines later, Dogen writes:

The actual Dharma teaching and Way of practice of the seven buddhas [Vipassi, Sikhi, Vessabhu, Kakusandha, Konagamana, Kassapa, and Gautama] necessarily include the transmission and reception of that reality and of that practice. Further, it is the internal and direct transmission of how all things are, and it is held in common by all the buddhas.

Giving and receiving, acknowledgment and recognition—that which comes from without and that which arises from within—transmission and reception from teacher to student and internal and direct transmission from within the buddha ancestors themselves.

The first transmission of the Dharma occurred between Shakyamuni Buddha and Mahakasyapa, and the first transmission of the Dharma happened when Mahakasyapa transmitted to Mahakasyapa. I want to explore the latter point of view today.

Sometimes, we say a lot about separation, by which I mean the feeling of separation between us and anything (or everything) else. In truth, there is no separation; it is only a feeling, though a powerful one and its presence can contribute to a great deal of suffering. Other times, we say only a little about separation, usually as a gentle reminder or a passing comment.

However we mention separation, we tend to highlight the mind’s role in producing this feeling. We might mention the mind’s discursive activity and its capacity for abstraction. Or we might focus on the way in which the mind drags attention from the present to the past, from the present to the future, from the future to the past, and from the past to the future through its “secretions.” It also pulls us into the present, by the way, but we tend not to say much about that; the mind is not an outright burden, despite the impression offered by some authors, teachers, and writers.

Or we shine a light on language. Perhaps you have heard someone say that language is “necessarily dualistic.” That is a fancy way of saying it has and creates division and difference—only with fewer words.

Consider the structure of a sentence: there is a subject, an object, and a verb that indicates the relation between the two. “Taishin rings the big bell.” How am I and the big bell related? By the action of ringing: when I bring the striker into contact with the big bell. But what about when I am not bringing the striker into contact with the big bell because I am outside moving woodchips? I still am, and the big bell still is, and we are still in relation to each other. But without some signification of that relation there arises an opportunity to believe the big bell and I are disconnected, separate, each existing independent from the other, and that we need to be brought into a relation once again.

The more time we spend in the world of words, concepts, and ideas, the more opportunities for this belief to become rooted and grow appear. When the belief takes root, you can see it at the edges of questions, such as How do I connect with so-and-so? How can I relate to such-and-such?

Response: You already do, but the form of that connection changes. Its shape is co-dependent on particular circumstances. We cannot quite predict the form in advance, though we try; it never quite matches our predictions, either. For that reason, we feel that there is separation, even though there is not; that we could somehow be “closer,” even though we could not. We feel that there is some barrier to break through or gap to bridge, when there is not.

If we become fixated on this feeling or if it comes to dominate our awareness, we can form the additional belief that something is lacking, that we are somehow incomplete and need to be made whole through the acquisition and continued possession of such-and-such an object. We begin looking outside of ourselves for something to cling to and hold on to, which runs counter to Dogen’s teaching: “Transmission is never exhausted; there is never a lack of enlightenment.” We are always attaining the marrow; we continually receive the treasury of the true dharma eye.

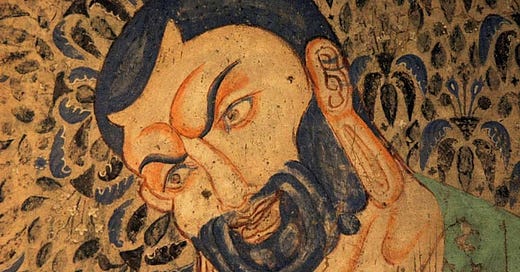

Recently, it occurred to me that it is not only the mind and the linguistic ways it oozes that facilitate feelings of separation. The eyes do it, too. The poet Pattiann Rogers writes in Eyes and the Sea:

I believe eyes were born of the sea, for, similar to the sea, they are quick to take in and give back with finesse and ingenuity. Both the sea and the eyes can bestow life and claim souls and enact tragedy. In the right circumstances, each can engender ice. Surely related, the sea and eyes alike establish distinctions simply by being—the earth from the heavens, the enfolded from the castaway, the calm from the storm. And each is composed of light at many levels, holding depth and surface with equal consideration. Both are so often the color of the sky, clear and opaque.

So many are the ways in which feelings of separation arise, though none of them deliberate. The mind’s activity is simply oozing—that is what it does. The eyes hold depth and surface and distinguish different waves of light “simply by being,” observes Rogers. Given how visual perception dominates our experience, it is unsurprising that we sometimes talk about seeing differently: with the mind’s eye or the third eye, through the eyes of practice, with the eyes of Jiko, which means “all-inclusive self” or “universal self.”

And sometimes, we feel that we do, for just a moment, see differently. Something shifts, and—what do we say?—distinctions drop away, everything is suddenly and immediately whole, and I am embraced, held gently in the arms of the universe! Maybe. But such experiences, if they ever happen, never last, and chasing them or trying to hold onto them only fuels feelings of separation.

I prefer to not continue in that direction. So, let us pivot and proceed in a different direction.

There is a pair of expressions in Zen that you may be familiar with: “Your thoughts are the scenery of your zazen (seated meditation). Your surroundings are the scenery of your life.” I have been practicing, reading, studying, and recently writing about Zen for fifteen years—and I do not understand these expressions. Fortunately, Zen is not about understanding, so I am free to use these expressions about the scenery of your zazen and your life as I see fit.

So, if you would indulge me, please take a moment to look around.

This. Is. It.

This. Is. It.

This is your life, and it is nothing other than this, just as it is, right now. You are not anywhere else; you are right here, in this space, sitting on cushions and chairs on this floor.

In the previous two Dharma talks, Case 16 of the Mumonkan has been mentioned. It reads:

The world is vast and wide! Why do you put on your seven-panel robe at the sound of the bell?

An appropriate response to this case could be: “The world is not that vast and wide!” I am here. The bell has rung. I respond accordingly.

All things in the entire universe of the ten directions are in their proper place, including you and me. In fact, because all things in the entire universe are in their proper place, so too are we in our proper places—this is like this because that is like that—for and at this singular moment. And for and at this singular moment, our lives are here in this place—this zendo (meditation hall), this talk, this sesshin, these trees, birds, squirrels, and each other are the scenery of our life. This. Is. It.

I spoke about separation earlier, by which I meant a feeling of separation that can arise in different ways. Because of this feeling, we might believe that something is missing. I also said that, in truth, there is no separation. Since there is no separation, nothing is missing.

There is no separation because we ourselves are the universal self, the total dynamic functioning of the universe. Few, perhaps, are able to express this truth better than Alan Watts, who wrote, “What [we] do is what the whole universe is doing at the place [we] call ‘here and now.’ [We] are something the whole universe is doing in the same way that a wave is something that the whole ocean is doing.” And similar to an ocean, the universe’s constant activity happens across distances farther than our eyes can see or minds can grasp—but for us, it is happening right here.

This is why Dogen can say, “Transmission is never exhausted; there is never a lack of enlightenment. [… Why t]here is nothing excessive and there is nothing lacking.” This is why transmission of the Dharma is not exclusively something that happens from without; it also includes that which arises from within.

Or, if you prefer—and since we are on the threshold—ultimately, there is no without, and there is no within. There is only a non-exhaustible, all-inclusive activity. For this reason, when conditions are just so, Mahakasyapa transmits to Mahakasyapa.

As I begin to close this talk, I feel the need to speak as plainly as I can about how Mahakasyapa transmits to Mahakasyapa. As I reached this point in my preparations, I was reminded of something Dogen writes in Shobogenzo Zuimonki about himself:

One of my greatest faults is that as soon as I pick up a pen, my writing naturally becomes elaborate and florid.

I do not quite feel this way. Still, I am aware of how, in the beginning, I try to write simple, straightforward sentences. But at some point, I can feel my feet start to leave the ground, and I begin flying among—even above!—the clouds. Allow me, then, to try returning to the earth.

Being right here does not require that we renounce all those things that foster feelings of separation: our dreams, fantasies, and ideals; tendencies to entertain hypotheticals or strategically plan for the future; ruminating on past events; the deep desire for control because we fear coming face to face with that which most frightens us.

It does, however, invite us to let each of these things (and more) rest in open hands. When our hands are open in this way, all things flow freely. When all things flow freely, our presence remains in the present. And when where we are is right here, how else can we respond but in the very way that Mahakasyapa did when Shakyamuni Buddha raised a flower?

Personally clarifying how this being right here manifests in our day-to-day lives is the internal and direct transmission of the Dharma from ourselves to ourselves. We can begin by attending to the scenery of our life, which is just as alive, vibrant, and bustling as anywhere else, as the following lines from Theodore Roethke’s A Field Of Light show:

Listen, love, The fat lark sang in the field; I touched the ground, the ground warmed by the killdeer, The salt laughed and the stones; The ferns had their ways, and the pulsing lizards, And the new plants, still awkward in their soil, The lovely diminutives. I could watch! I could watch! I saw the [connectedness] of all things! My heart lifted up with the great grasses; The weeds believed me, and the nesting birds. There were clouds making a rout of shapes crossing a windbreak of cedars, And a bee shaking drops from a rain-soaked honeysuckle. The worms were delighted as wrens. And I walked, I walked through the light air; I moved with the morning.

If you benefitted from this offering, consider reading these others: