Transitions facilitate opportunities for reflection, and I am sitting with potential directions of movement in recovery for 2025. Never mind that we are one month into the year. All that unfolds unfolds in its own time, always.

The potential directions are without goals; there is no intention to move in a direction spurred by hope of reaching a predetermined destination. There might be movement in some direction because of an intention, of course, but without the accompaniment of hope. Similar to Plato’s aporetic dialogues, it is exploration, inquiry, and investigation that encourage movement. Without fail I will arrive somewhere, but that somewhere is not seen in advance—at least, not in full color nor with appreciation of its fine details. Goals tend to obstruct clear seeing and deep appreciation; they can hinder our capacity to remain “open to surprise,” as one Zen teacher describes it. Sometimes, we become focused on whether an experience fits how we want it to or judge it should be, rather than meeting what did arise.

I shall do these things, then this will happen. It will look like this.

I will undertake this effort, then such-and-such should be complete. I want that, that, and that to be part of it, too.

Still, it is not appropriate (or realistic) to banish all “wanting” and other shapes of desire. Similarly, judgments that something “should” or “should not” be the case are necessary (though not necessarily all the time). In an old poem, we read:

With many words and thoughts You miss what is right before you. Cutting off words and thought Nothing remains unpenetrated.

“If neither extreme, then what?” is the invitation. In a similar spirit, I ask: in what direction should I move for now, joined with a readiness to adjust when appropriate?

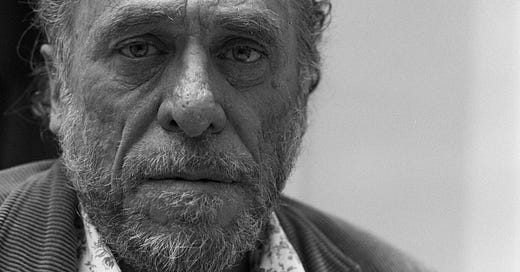

Recently, I was sitting with the poem “How Is Your Heart?” by Charles Bukowski. Odd, you might say, for someone in recovery. Odder still, perhaps, for a reflection on recovery, for a friend of mine once observed, “Bukowski was never sober a day in his life!”

Maybe.

One aspect of a person, however, need not—in fact, it cannot—determine everything about that person. The adage to refrain from judging books by their covers holds not only for books but people, too.

The poem reads:

during my worst times on the park benches in the jails or living with whores I always had this certain contentment— I wouldn’t call it happiness— it was always an inner balance that settled for whatever was occurring and it helped in the factories and when relationships went wrong with the girls. it helped through the wars and the hangovers the back alley fights the hospitals. to awaken in a cheap room in a strange city and pull up the shade— it was the craziest kind of contentment. and to walk across the floor to an old dresser with a cracked mirror— see myself, ugly, grinning at it all. what matters most is how well you walk through the fire.

Six months ago, when frightened and in the fires of transition, I held the final lines close, reciting them as if they were a mantra. I sought comfort, security, and confidence. What I discovered, however, was the strength to remain slow and steady, to “walk like an elephant,” as I am becoming fond of saying. I committed to creating only necessary waves—and I maintained that commitment.

Here, I want to explore the condition of contentment that is Bukowski’s focus and how it differs from resignation. Where is the boundary line, even if tentatively marked, between these two states? Or if marked with certainty, how fuzzy is it? How can I tell whether I am content or resigned? What signs appear on the path that suggest one or the other?

My “worst times” were not spent on park benches or in jail. Instead, I would sit, sick and shaking, in liquor store parking lots, waiting for the open sign to flicker on. I never grinned into a cracked mirror on top of an old dresser. But a similar grin was reflected in my bathroom mirror near the end of seven-to-ten day benders. My eyes were bloodshot, skin tight, and facial hair crusty with the (former) contents of my stomach. That grin—my grin—did not arise from inner balance. I had settled, in a sense, but the dependent cause was defeat.

Defeated how? Simple: I was “stuck.” I wanted to move in a different direction—preferably a better direction, possibly a worse direction, but definitely, decidedly different. I wanted to end a cycle that admits of several complimentary descriptions: rising and falling, happiness and misery, sober and drunken stupor. There was great desire but small follow-through; despite (admittedly half-hearted) efforts, I could not succeed.

But stuck how? The sense is ambiguous. Was it just external circumstances that obstructed movement? There was a once-in-a-century pandemic, after all, that brought fear and anxiety and loneliness and isolation. I felt physically trapped, too, in one of Indiana’s countless cornfields.

Perhaps.

An alternative is that the “just” is not quite right. If nothing is anything by itself and everything is anything through the totality of all conditions at some one time, then that state of stuck-ness was also born from the beliefs and feelings of this heart-mind. (See the previous.) Its emergence was (or: is) relational, influenced by the orientation of that heart-mind in the cornfield.

There was a familiar pattern of the heart-mind as well. I set high expectations—in three days, this; in ten days, that—and with remarkable consistency did not meet them. One-off setbacks are manageable, and an unfailing part of life. Twenty, fifty, or I-simply-stopped-counting-offs present challenges and, coupled with a depressed mindset nurtured by alcohol abuse, can foster an outright unmanageable situation. I became entangled in narratives where the inner critic had free rein to belittle, bully, and condemn with a precision fueled by well-nourished self-hatred.

I was not only trapped on the outside. I felt trapped on the inside, too, and I hated what I had become. I did not find myself owing to lousy luck in the “worst times” and would not describe myself as someone to whom these things “just happened.” For I actively, deliberately created them—and I could not stop even though I was aware of my actions and their consequences. This is one form of inner torment some of us confront in active addiction. So, I resigned myself to continue moving with the world in this way. I would create harm for others and myself; I would utter “no shame” as I walked into the liquor store first things in the morning, unkempt and unwell. I was off-balance, and I would remain there.

As I stumbled toward a path of recovery, I heard somewhere that alcoholism is a form of suicide on an installment plan. I understand that. I wanted the suffering to end, and continued diving to the bottom of bottles determined to end it by drowning.

I felt irreversibly stuck.

Of course, I was never stuck. Moreover, never can I be stuck. And asserting this does not invalidate how I felt at the time or how I feel now as I recall those days. Recognition that what I felt to be the case and what was the case are incongruous does not require dismissing what was felt or what was. It is not necessary to classify one as “right” and the other as “wrong.” The whole of what was (and is) is spacious enough to hold seemingly contradictory statements.

In the same old poem, we read:

Enlightenment has no positive or negative. The duality of existence Is born from false discrimination, Flourishing dreams and empty illusions.

Instead, I can set aside the assumption that congruity is a meaningful standard by which to evaluate these experiences, the circumstances in which I found myself, and situations where I played a part, whether predetermined or spontaneous.

What happens when I am oriented in this way?

First, I find support for a central teaching of the Lankavatara Sutra: I create a world formed by and populated with the projections of this heart-mind. Without (much) thought, I impose categories and classifications on the myriad things. (The “myriad things” are not even myriad things, by the way, nor are they not not myriad things.) Then, I form judgments about how the world—the world I created—is and assign responsibility for its current state to someone or somewhere else.

I become Shariputra, who, in the beginning of the Vimalakirti Sutra, is awakened to these truths with help from the Buddha and the Brahmin Sikhin. Where there was disgust, there is now delight; where there was doubt, there is now quiet confidence and understanding. Or, as Shariputra himself says

I see it! Here before me is a display of splendor such as I never before heard of or beheld!

You might exclaim the same if, suddenly, the billion-world galactic universe was transformed into a huge mass of precious jewels, with an ungraspable number of gem clusters, and those in the assembly were seated on jeweled lotus thrones.

The sudden and the splendor signify how immediate and extreme transformation can be once the construction is seen for what it is—no different from horns on a rabbit. The way the teaching cuts in two directions and, simultaneously, everything collapses together is thunderous.

Second, and less philosophical and theatrical, I enter a field of grace. The inner critic of which I wrote above rests, their voice a whisper. I begin to see that the critic was not a combatant, but a comrade, their hysteria a natural response to the cage. “Break free!” the critic cries, but the imperative is received in the form of an insult. Blame and fault need not sprout nor bloom, for the field is—and ever was—full of compassion’s flowers. And I can rest in them, alongside the critic, too.

I had thought to end this post in the field. There was something fitting about it. But I had also planned to write about impermanence, one of the Three Marks of Existence. (The other two are suffering and non-self.) For while I was sitting with the trio of resignation, defeat, and stuck-ness, and how that trio might remain close to but different from contentment, the following found its way to me:

Don’t ever lose sight of impermanence. If you truly see impermanence, you are a Buddha with each exhale and a Buddha with each inhale. You have everything then and there. No reason to think about persevering in the future.

These are the words of Kodo Sawaki, an irreverent Zen master.

In active addiction, I projected permanence far and wide—and close to home. Sometimes, I convinced myself that my present condition was a forever condition. Then, I lamented that “sure and trusted truth.” Other times, the assumed permanence was not of the everlasting variety; its duration was simply longer than I cared for at a particular time. Above I mentioned that I wanted things to change somehow, but an accurate statement might be: I wanted things to have changed already (and with minimal effort from me). I wanted what I wanted, when and how I wanted it, and I wanted it sometime in the (distant) past. Please, and thank you.

I had lost sight of impermanence.

Or had I?

At the time, I had been practicing Zen for eight(ish) years. I was not unfamiliar with the concept, the idea, the teaching. Perhaps there is something to be gleaned from the word “truly”: “If you truly see impermanence […].” What does this mean? What is the significance of the adverb here?

My suggestion—and it is only a suggestion—is that when impermanence is truly seen, then there has been direct insight into reality and that insight has become integrated with the whole of our being. For it is not a concept, an idea, or a teaching that we see; it is not words scribbled or printed on a piece of paper. Rather, it is that to which the letters, words, and sentences encourage our attention—the proverbial finger pointing toward the moon or the moon’s reflection in the water calling us to look (read: wake) up. From the head’s crown to the soles of our feet and everywhere in between, flowing from and returning to the heart-mind, the truth expressed in the words and phrases circulates.

Everything that arises perishes. Youth becomes old age, health becomes sickness, and life becomes death. We read in the Five Remembrances that all that is dear to us and everyone we love are subject to change. There is no way to escape being separated from them. But how often do we remember the Remembrances? How often are we integrating these insights into our day-to-day lives?

In some cases, sickness becomes health, spiritual friends once at a distance return close to hand, and a feeling that practice has grown stale burns up, creating energy and enthusiasm. A freshness blooms.

Recognition of ever-present and universal instability quiets craving. For we hunger and thirst after something other than what is right here. Something better, usually, something worse, sometimes, and when there is an accompanying desire to punish ourselves. A little less sour and a little more sweet, a touch of sunlight to pierce through an overcast’s gray, or pleasant odors to counteract what causes the nostrils to curl.

I used to want another six beers and just as many shots of liquor to dull my six senses. Facing my life as it was was too painful, and with such heavy sedation I could escape into empty dreams and encourage fantastic illusions.

The truth was and remains, however, that there is nothing else to experience than what is right here and nowhere else to go. The past is no more; the future is not yet. The present moment of others, too, is their present moment, arising in conjunction with the activity of their heart-minds and their bodies. I cannot be where they are, and should I endeavor to shift my position to that place, what was there has passed and something else appears.

Everything vanishes, every time. All is different, always. And I have all that I can ever have, necessarily.

And—

And, lest it be not said, in all this conjoined, constant transformation the referent of “I” cannot be other than it is in that moment and is never the same in the next moment. The constitution of the skin bag, the feelings and thoughts of the heart-mind, and awareness itself shift and shimmy and never stop. There is no “me” who can be tied down, for this “I” is just as formless as a eunuch’s erection.

The other side of all-encompassing change is freedom. Liberation is not found when we rest of stable ground, but as we learn to ride life’s waves, confident in our ability to curve and cut in response to every new set of conditions. There is never a need to persevere, as there is nothing to persevere with or through; whatever is is just as fleeting as stars at dawn.

When we let our desires be carried away in a breeze, we find “an inner balance that settle[s] for whatever [is] occurring.” That sounds crazy, I am sure. It runs counter to many conventional ways of orienting ourselves—and that is OK.

How fitting that Bukowski would call it

the craziest kind of

contentment. You may also enjoy:

This is lovely, lovely writing and gives me a lot to think about. Thank you for this gift, Taishin! Thanks for walking like an elephant, and joining our NBZ field.

-Rentai

How interesting to consider the felt realization of impermanence as an element in recovery. Thank you for this deep dive into Dharma and addiction, and for sharing so honestly from your own life, Taishin.