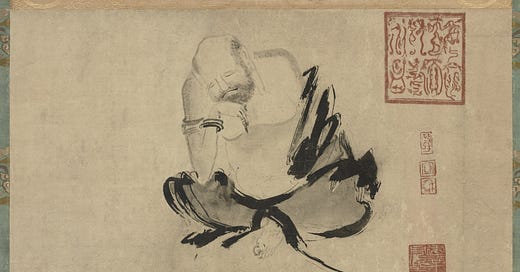

Bodhidharma had several disciples. Dao Fu (who attained the master’s skin), Zong Chi (who attained the master’s flesh), and Dao Yu (who attained the master’s bones) are mentioned in a story from the Compendium of Five Lamps. But Dazu Huike (487-594 CE), who attained the master’s marrow, is singled out as the successor and, therefore, the second Chinese ancestor.

The record has it that Huike demonstrated his determination and sincerity to study with Bodhidharma by cutting off his left arm and presenting it to Bodhidharma. Why presenting a severed limb—his severed limb, no less—to a (prospective! prospective!) teacher is a sign of resolve and pure intent is not altogether beyond me. You will not, however, find me in a similar position as I search for a new teacher.

It is said that religious or spiritual practice “requires sacrifice.” Traditionally, practitioners are asked to forego conventional comforts and adopt a life of modesty and simplicity; the means of securing a particular sort of reputation are set aside, too—usually meaning wealth, political power, and social influence; and in some cases, romantic partnerships are prohibited. Although not exhaustive—not mentioned are features of the historical context, cultural and societal climate, and we might wish to learn more about Huike, too—the list serves well enough to offer outlines of a space in which Huike’s demonstration can find its place, even if near the edges.

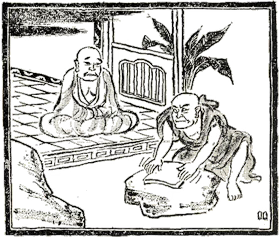

After becoming Bodhidharma’s disciple, Huike requested of Bodhidharma that he [Bodhidharma] pacify his [Huike’s] mind.

Huike said, “My mind is anxious. Please pacify it.” Bodhidharma replied, “Bring me your mind, and I will pacify it.” Huike said, “Although I have sought it, I cannot find it.” Bodhidharma then said, “There, I have pacified your mind.”

I am tempted to say, giving way to skeptical tendencies, “If only it were that easy.” But there is no (good) reason to suppose that the pacification of Huike’s anxious mind was “that easy.” A great effort had been made; Huike tells Bodhidharma, “Although I have sought it [i.e., my mind].” A search was undertaken by someone who (supposedly) dismembered themselves to show their sincerity.

How long did Huike search? How much energy did he expend? Precise answers are not available, and they do not matter.

What matters is the recognition that the exchange between Bodhidharma and Huike capped a period of diligent practice. I am confident that Huike was sometimes frustrated, but he just. kept. going. I am convinced that he felt doubt and insecurity, but he just. kept. going. And when conditions were suitable, there was a shift.

But what shifted? What did Bodhidharma intend to impart to his disciple and, in time, successor? If nothing else, we can surmise that the transmission succeeded, for we find a record of a similar exchange between Huike and an unidentified layman suffering a terrible illness.

The layman said, “My body has been wracked by a terrible illness. I ask that you absolve the transgression I’ve committed that has caused this.” Huike said, “Bring me the transgression you’ve committed and I’ll absolve it.” The layman said, “I’ve looked for the transgression but I can’t find it.” Huike said, “There, I’ve absolved your transgression. Now you should abide in Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.” The layman said, “Seeing you here, I know what is meant by ‘Sangha,’ but I still don’t know what are called Buddha and Dharma.” Huike said, “Mind is Buddha. Mind is Dharma. Buddha and Dharma are not two different things. Along with Sangha, they comprise the three jewels.” The layman said, “Today, for the first time, I realize that my transgression was not internal, was not external, and was not in between these two states. It was entirely within mind. Buddha and Dharma are not two things.”

The layman would become Jianzhi Sengcan, the third Chinese ancestor.

“Bring me your mind, and I will pacify it,” says Bodhidharma.

“Bring me the transgression you’ve committed and I’ll absolve it,” says Huike.

These are not quite the same as Gutie’s One Finger. At the same time, they are not all that different.

As I sat with the similarity, I felt (seemingly simultaneously) curiosity and disappointment. I have an aversion to repeat performances: been there, done that, got it. Still, I could not resist looking for an underlying message. What did Bodhidharma transmit to Huike, who, in turn, transmitted the same to Sengcan? In both cases, what was sought was not found—Huike could not find his mind, and Sengcan could not find his transgression. But how does that pacify anxiety? How does that cure a body’s terrible illness? A teaching was offered in each exchange—but what was it?

The questions are not merely academic but simultaneously practical. My days as a university professor are gone, but I still enjoy textual analysis. Sometimes, we call this “reading between the lines.” More often, though, I engage with a passage as I would a piece of visual art. How does it look if I sit here or stand there? What about in this lighting or from this distance? Concerns with much-prized objectivity are absent; I desire to experience simply what is here. And so, sometimes, the text serves as a mirror: it reflects me to me and permits me to see what was not previously visible.

Precious is the ability to redirect light.

I, too, am occasionally wracked unwell by anxiety and feel ill after acting or speaking without care and skill. It would be fantastic (or so I assume) if a panacea were always to hand.

The questions are also existential. They reveal a lingering fixation on losing an identity and what, if anything, to do about it. How do I continue working with a nagging feeling of loss?

I used to live and practice in a container that helped create and support a specific identity. Then, I left because I became unwilling to endure several intolerable conditions manifested and supported by individuals principally responsible for maintaining the container’s health. As a result, I no longer weed garden beds or move wheelbarrows of woodchips to replenish a worn meditation trail. I also no longer lead sewing practices or weekly Dharma studies, train Sangha members to serve here or there, or welcome newcomers. Leading Oryoki practice and officiating Sunday services are gone, too. Many activities with a clear connection to the expression of the Dharma are no longer part of my daily or weekly activities.

It is understandable, therefore, that I would become entangled in the question: Where is the connection now? Where is the expression in the activities that now populate the days and weeks?

Jion Osho, in his introduction to the Ten Oxherding Pictures, writes that “to grasp the principle of the Dharma is to transcend sect and overcome doctrine just as a bird in flight leaves no traces.”

Nanyue Huairang tells Mazu Daoyi that his sitting activity “stud[ies] the Dharma gate of the mind-ground, and this activity is like planting seeds there. The essential Dharma of which I speak may be likened to the rain that falls upon the seeded ground.”

What is this formless Dharma that admits of boundless manifestations yet remains undefiled? Why does it feel plain impossible to perceive it even though it is continuously, indiscriminately present?

We are told that Bodhidharma gave Huike a copy of the Lankavatara Sutra along with the robe and bowl. All he needed, apparently, was to be found within it.

The sutra has two central teachings. First, it stresses the primacy of direct experience, sometimes called “self-realization,” at the heart of the Zen tradition. Second, it argues at length that the world we regard as real is a “projection of our own mind.” Put differently, we are often entangled in the perceptions of our own minds.

From one more point of view, if the Diamond Sutra emphasizes the impermanence of all things and the Heart Sutra reveals the emptiness of all things, then the Lankavatara Sutra teaches that there are no “things” to be impermanent or empty. It is also not the case that there are no “things” to be impermanent or empty, for even those categories foundational to our conceptual structures—here, existence and non-existence—are projections (or perceptions) of our own minds. Even talking about the teachings of the sutra requires the use of that which the sutra subverts. Arguably, it is unique in that way.

If this is the teaching imparted, then Huike’s story, his relationship with Bodhidharma, and Bodhidharma’s teachings raise different but related questions. Namely, how do we talk about that which was transmitted without falling too far in one direction?

Sengcan would later write near the beginning of “Faith In Mind”:

Do not chase the conditioned Nor abide in forbearing emptiness. […] Just say, “Not Two,” For in “not two” all things are united, And there is nothing not included.

Of course, we can say “Not Two” and with confidence, as

The wise ones of the ten directions Have entered this great understanding, An understanding that neither hastens nor tarries.

But from time to time, we need to say something other than “Not Two.” We need to say “Hello!” and “Goodbye!” and “I love you!” and “I am sorry.” We need to encourage new relationships and transition from those that have run their course. How does this happen while simultaneously “embod[ing] no coming or going” and “not perceiving refined or vulgar”?

I find glimmers of a way in the verse Huike spoke to Sengcan when transmitting the Dharma:

Fundamentally, karmic conditions have given rise to the ground That allows the seeds of flowers to grow. Fundamentally, nothing has been planted, And flowers have not grown.

Simultaneously, there is an acknowledgment of the constructed karmic-driven world and the formless reality with which it meshes but does not (and cannot) contain. Simultaneously, there is division without separation. Simultaneously, there is a stern seriousness with the freedom of play.

When clinging and grasping settle down, naturally

In accord with [our] fundamental nature [we] unite with Tao, And wander the world without cares.

Its manifestation is gentle speech, open hands, and light footsteps, all beneath mischievous eyebrows and knowing eyes. And what do these eyes know?

There is no yesterday, no today, and no tomorrow.

You may also enjoy reading: